D. Paul Schafer, Founder and Director World Culture Project (www.WorldCultureProject.org)

KEY TO LIFE AND LIVING IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Over the last two and a half centuries, developing economies has been accorded the highest priority in the world. While countless benefits have been derived from this, it has become clear over the last few decades that the costs of developing economies are starting to outweigh the benefits and this could get much worse in the future. Hence the need to make the transition from developing economies to cultivating cultures as the most effective way to deal with this problem in the future.

I DEVELOPING ECONOMIES

While the development of economies is the result of many factors and contributions from countless people and organizations, there is no doubt that some key factors and the ideas of a number of distinguished economists have led the way in this regard. This is because they created the theoretical and practical foundations as well as made seminal contributions to developing economies and the economic age we are living in today. (1)

No economist was more important in this respect than Adam Smith. In his famous book The Wealth of Nations, Smith set this remarkable process in motion and gave it a powerful push in the right direction when his book was published in 1776. (2) This is because Smith was the first person in the world to claim that phenomenal increases could be achieved in the production of goods and services and creation of material and monetary wealth by “breaking wholes into parts” and people and organizations “specializing on very specific production functions.” He clinched the case for this by using the example of a pin factory and demonstrating in numerical terms that many more pins could be produced every day if people and factories specialized on specific production activities rather than generalized on many or all production activities. While breaking wholes up into parts and specialization – or the “division of labour” as Smith and most other economists called it at that time – had been going on for millions of years due to people’s insatiable curiosity and incredible creativity, Smith brought these two ideas together and into prominence by turning them into two of the most powerful factors and features in the world today.

These contributions help to explain why the Industrial Revolution took off in leaps and bounds about the same time that Adam Smith’s famous book and evocative theories were published and led to phenomenal increases in the production of products, utilization

of natural resources, creation of millions of factories, and a colossal expansion in material and monetary wealth compared to earlier times.

Another one of Smith’s major contributions was making a strong distinction between what he called “productive” and “unproductive” labour. According to Smith, productive labour is labour that results in the creation of tangible and material products, such as those produced by people working in agriculture and industry. Unproductive labour is labour that doesn’t produce tangible and material products, such as the activities engaged in by artists, teachers, religious leaders, civil servants, and the like.

Coupled with the unbelievable increases that were taking place in production and consumption created by productive labourers, Smith made a compelling case that people should pursue their own self-interests, accept the fact that there is an “invisible hand” at work to ensure that everything turns out for the best in the end, and laissez faire and free trade are the most effective policies to pursue in domestic and international affairs. This explains the colossal expansion that took place in the supply and demand for products and resources in the western world and eventually most other parts of the world as well.

Smith’s views on this subject were strengthened considerably when David Ricardo, who was also an economist as well as an astute politician and clever diplomat, appeared on the scene. Ricardo’s contribution to developing economies resulted from formalizing economics as a distinct and independent discipline in his book The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation published in 1817. (3) Not only did Ricardo confirm Smith’s belief that economics should be given the highest priority in countries and even above politics in his view, but also he developed and promoted the law of comparative advantage which was based on maximizing the benefits that can be realized from international trade for all countries and creating even more material and monetary wealth.

Following on the heels of Adam Smith and David Ricardo was Karl Marx, who was an economist too, in addition to being a philosopher, social theorist, and powerful international activist. (4) Marx was best known at the time and even today for his contempt of capitalism and capitalists, deep concern for labourers, and especially his commitment to communism which ended up dividing the entire world into capitalist and communist or socialist components for the better part of the twentieth century. He also embraced Smith’s distinction between productive and unproductive labour but carried it much further. He did so by focusing on what he called “the modes or means of production” and introducing capitalists and capitalism into the equation alongside labour and labourers at a time when the Industrial Revolution was in full swing. Marx claimed that all societies can be divided into two distinct parts: an economic base; and a non-economic superstructure.

According to Marx, the economic base includes everything created by productive labour and capital, whereas the non-economic superstructure includes everything that results from unproductive labour. Writ large, this led Marx to conclude that the past can be interpreted in economic terms through what he called “the economic interpretation of history.” (5) He also believed that his base-superstructure theory was true not only when he was living and working, but it is always true and therefore true at all times and in all places. Since the only way the non-economic superstructure could be created in Marx’s view was when the economic base yields a “surplus” of production over consumption, this is what made it possible to bring the non-economic superstructure into existence. In other words, the economic base is by far the most important factor in societies, countries, and the world, as well as the cause and basis of everything else. As a result, all attention and the highest priority should be given to growing the economic base (economies) as rapidly as possible because everything derives from this, depends on it, and can be traced back to it in the end.

This distinction between the base and superstructure in general and productive and unproductive labour in particular led around the same time to making a strong distinction between what came to be known as “the basics in life” and “the frills in life.” The basics were seen in terms of the economic base and productive labour and therefore what life and living were really all about; the frills were seen in terms of the non-economic superstructure and consequently what people did in their spare time. While it wasn’t realized at that time, this turned out to be one of the most powerful forces in the world because it put the emphasis on the material side of life – which is why Marx’s economic interpretation of history is also call “the materialistic interpretation of history” – and marginalized the non- material side, such as the arts, humanities, heritage of history, culture, and related activities.

Soon after Karl Marx was Alfred Marshall, whose book Principles of Economics was published in 1890. (6) Whereas Smith, Ricardo, and Marx were interested in what is called macroeconomics today – or the study of economics and economies in comprehensive terms and how they function – Marshall was interested in what is called microeconomics, or that part of economics which is concerned with the laws of supply and demand, the determination of prices, value theory, the behaviour of producers and consumers or buyers and sellers, the operations of companies and corporations, profits and profit maximization, and the functioning of different types of markets. According to Marshall, economics – or political economy as he and most other economists called it at that time since these two areas were closely linked together – is “the study of mankind (humankind) in the ordinary business of life. As such, it examines that part of individual and social behaviour and action that is most closely connected with the production, distribution, and consumption of the

material aspects of well-being.” (7) As a result, Marshall’s theory of value states that the price and output of a product are determined by the interaction of supply and demand in the marketplace, which he often compared to the functioning of a pair of scissors since both blades play a role in the cutting process.

For Marshall, the ideal economic system functions most effectively when people are deriving maximum satisfaction from their purchases in the marketplace, corporations are maximizing their profits and competing as vigorously as possible, and the entire system is in a state of equilibrium. By focusing on matters like this, Marshall brought economics and economies into the human realm, the everyday lives of people, companies, and countries, and much closer to home. It reminds me of the fact that economics was initially deemed to be “household management” by the Romans more than two thousand years ago.

Finally, there is John Maynard Keynes. He was an English economist much like Marshall and many others who also had a powerful effect on the development of economies as it is seen, dealt with, and practiced in theoretical and practical terms today. Keynes emerged on the international scene and rose to prominence during the Stock Market crash in 1928 and the Great Depression from 1929 to 1939. This resulted from all the difficult economic, commercial, and financial problems that were being experienced at that time, such as incredibly high rates of unemployment, millions of people and companies going bankrupt, wild fluctuations in commercial and financial activity, dreadful food shortages, and, in short, an economic system that was in a severe state of disequilibrium and disarray.

Keynes set out to explain why this was happening, what was wrong with the economic system, and what could be done about it. This led him into an intensive study of what he called the “real economy” and the “money economy,” and, as a result, the intimate connection between saving, investment, interest rates, monetary policy, national income and expenditure, and especially the role governments should play in dealing with difficult problems like this and many others. These problems were addressed in Keynes’ most important and timely book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money published in 1936. (8) This book is concerned with how difficult problems like this can be dealt with most effectively through an array of monetary, fiscal, and government policies.

While most economists and politicians were still strongly committed to the beliefs of Smith, Ricardo, Marshall, and many others that solutions to most if not all economic and financial problems should be left largely to “the marketplace” and “the iron-clad laws of supply and demand” without too much interference, Keynes made a powerful case that governments should get actively involved in the economic and financial affairs of nations. This was best achieved by spending public funds and using a combination of monetary,

fiscal, and funding policies to give economies a real boost when they needed it the most. For Keynes, the most important factor is the level, structure, and character of what is called “aggregate demand” today, or the total of consumer, corporate, and government expenditure, saving, investment, interest rates, additions and withdrawals from the income stream, liquidity preference (people holding on to their money rather than spending it), and especially government expenditure which is still the case today. For Keynes, governments should create budgetary surpluses in times of prosperity in order to have the funds necessary to spend on economic recovery and revival during recessions and depressions.

Looking back on these developments and many others over the last two hundred and fifty years, this is primarily where matters stand today with respect to developing economies and the crucial role they play in people’s and countries’ lives by creating goods, services, and material and monetary wealth, despite the fact that this is now a far more complicated and difficult matter than it was in the past. In order to develop economies effectively, active involvement in this process is imperative on the part of consumers, corporations, and governments, and therefore all the billions of people and organizations that depend on economies, keeping them growing, and satisfying their needs. While many benefits have been derived from this since The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776, all the numerous recessions, depressions, stock market crashes, business cycles, inflation, government debts, and wars that have occurred since that time confirm the fact that economies can easily get off track and cause difficult problems for people and countries.

Here, in a nutshell, are the most powerful and fundamental ideas, factors, and forces driving the world today. It includes awarding the highest priority to economics and developing all the diverse economies in the world; breaking wholes into parts in order to capitalize on their remarkable potential and productive capabilities; specialization; treating people as consumers first and foremost; placing a very high priority on corporations as the producers of goods, services, and wealth; profit maximization; relying largely on markets and the marketplace to regulate economic activity; depending on governments to deal with any breakdowns in the economic system through a variety of monetary, fiscal, and funding policies; and producing as much material and monetary wealth as possible.

II ASSESSING THE WORLD SITUATION AND PRESENT PREDICAMENT

Without doubt, development of all the economies in the world and the global economic system is the greatest human achievement in history. Billions of people and numerous countries have had their standards of living and quality of life improved immensely as a result of developments in the economic domain ever since Adam Smith laid the theoretical and practical foundations for this. It is a phenomenal achievement that

cannot be matched by any other human achievement, be it explorations in outer space, landing astronauts on the moon, inventing the car, airplane, telephone, television, or the cellphone, creating remarkable works in the arts, sciences, education, and technology, inventing the James Webb telescope, artificial intelligence (AI), and digital technologies, or constructing giant skyscrapers, magnificent cathedrals, and exquisite mosques. It is a colossal achievement that far outweighs anything else created by human beings.

This raises a very important and timely question. If the development of economies and the global economic system is so phenomenal, why don’t we just go on developing economies and this system and refining them in areas where they are deficient?

This would be possible except for one quintessential problem. It is the lack of consideration that was given to the environmental, human, and cultural “context” in which all economic developments have taken place over the last two hundred and fifty years.

While adequate attention was paid to agriculture, industry, technology, mechanical inventions, natural resources, people as consumers, companies as producers, politics, and governmental economic policies during this time because they were essential components of the development of economies and the global economic system, economics developed largely as a “free-standing and independent discipline” with virtually no attention given to its broader, deeper, and more all-encompassing context. This is primarily because most economists, politicians, and world leaders assumed or believed that the “marketplace” would resolve any problems arising from the operations of economies or resulting from it.

Regrettably, this has not been the case. Over the last four or five decades, it has become steadily more apparent that we are paying a colossal and rapidly escalating price for misreading this situation and assuming that the marketplace will look after and solve most if not all problems that arise. Not only is the natural environmental in all its diverse forms and manifestations creating an incredible amount of devastation and destruction in the form of horrendous floods, hurricanes, typhoons, storms, forest fires, the sinking of coastal areas, and the decimation of millions of agricultural crops, but also it is obvious that the huge inequalities and disparities that exist in income and wealth throughout the world will not be solved by the marketplace and will likely get much worse in the future. Added to this is the possibility of experiencing many more conflicts and wars between people and countries as natural resources are depleted, arable land becomes coveted and scarce, and the finite capacity of the earth and its diverse eco-systems is approached.

As problems like these continue to pile up and multiply considerably and others begin to manifest themselves more frequently throughout the world, it becomes steadily more evident that these difficulties will not be solved by developing economies and the

present global economic system. This is because they were created and designed to produce goods, services, and material and monetary wealth and not created or designed to deal with problems as vast, complicated, multidimensional, life-threatening, and dangerous as this.

Is there a way out of this present predicament and difficult dilemma? Indeed, there is, but in order to realize it, it will be necessary to see and interpret the world situation from a very different and all-encompassing perspective. As Albert Einstein said many years ago, “we can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking that created them.”

The answer to this dilemma and predicament lies in the realm of culture, not economics. It involves seeing and dealing with life and living in the world in cultural and holistic rather than economic and partial terms, defining culture in general and cultures in particular as “complex wholes” and the “total ways of life of people and countries,” according culture and cultures a central rather than marginal role in the lives of people and the world of the future, cultivating all the diverse cultures in the world in breadth and depth and situating them effectively in the natural, historical, global, and cosmic environment, and entering a cultural age in the future and enabling it to flourish.

Interestingly, when anthropologists began travelling to many different parts of the world in the latter part of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century to analyze societies and countries in depth and on the ground, they discovered that people had words for all the specific activities they were engaged in as they went about the process of meeting their individual and collective needs and working out their complex association with the natural environment and the world. However, what they didn’t have, and needed desperately, was a word that described how all the multifarious and diverse activities they were engaged in were woven together in different combinations and arrangements to create wholes and overall ways of life made up of countless interacting and interconnected parts. The word they chose to designate this all-inclusive process and holistic phenomenon was culture, not economics. This is because anthropology as a discipline was seen and defined in terms of all aspects and dimensions of people’s lives, living, and ways of life and not just some important aspects and dimensions of it seen and defined by economists.

This is why Edward Burnett Tylor, who is regarded by many scholars to be one the first anthropologists in the world if not the first, defined culture formally as a discipline and reality in 1871 as…. “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man (people) as a member (members) of society. (9) Tylor defined culture and cultures in these terms for a very specific reason, namely to describe and explain what he and many other anthropologists discovered when they examined people, societies, and countries in real

terms, on the ground, and in a great deal of detail. Regrettably, this definition was largely ignored at that time and since that time because the world was immersed in, preoccupied with, and largely dependent on the thoughts, ideas, and ideals of numerous economists and all the multifarious benefits that could be derived from this.

The fact that culture’s all-inclusive capacity focuses on the whole and not just a specific part of the whole should be applauded and capitalized on rather than downplayed and ignored. As Ruth Benedict, the distinguished anthropologist and cultural scholar pointed out many years ago in her book Patterns of Culture, “The whole, as modern science is insisting in many fields, is not merely the sum of all its parts, but the result of a unique arrangement and inter-relation of the parts that has brought about a new entity.”(10) This new entity and insightful statement was reinforced later in her book when she said, “The whole determines its parts, not only their relation but their very nature.” (11) In other words, if you change the whole you change the parts.

If this perception and definition of culture as the complex whole or total way of life of people and countries had been recognized, adopted, and utilized when it was first defined in print by Tylor and confirmed by numerous other anthropologists since that time, the world would likely be a much different place today. The focus would be on the holistic perception and definition of culture and by implication cultures far earlier. Moreover, attention would have been directed to the fact revealed by countless anthropologists that people and countries that do not take the natural environment and the impact they have on it fully and forcefully into account run the risk of over-extending themselves, collapsing, and even disappearing entirely from the world.

Let’s not ignore this sage advice and keen insight into the fundamental relationship between people and the natural environment a second time by failing to recognize that culture and cultures have a much more legitimate claim to being seen and treated as the complex whole and total way of life of people and countries than economics and economies which only see and treat this in partial terms as Alfred Marshall and virtually all other economists define it. In fact, it is rapidly becoming apparent in more and more regions and parts of the world that culture and cultures, not economics and economies, are the real foundations of human existence on earth and the essence of life and living in the world for all species and not just the human species, as well as the fact that economics and economies are really “part of culture and cultures” when they are seen and dealt with in holistic terms rather than the other way around which is the case today. (12) When the distinguished scholar and author, Goethe, said, “it is with the eye more than any other human organ that I learned to see and comprehend the world,” he put his finger on the crucial importance of

this matter. For he opened our eyes to seeing the world and everything in it from a holistic, cultural perspective rather than partial, economic perspective, and therefore seeing “the big picture” and not just a very important part or parts of it.

One of the most essential benefits of this holistic perspective of culture is the ability to see, comprehend, and deal with the big picture of the world, something that was and still is very much lacking in the world today. This ability not only makes it possible to see and understand the world in all-encompassing terms – which is of vital importance at present and going forward into the future – but also makes us conscious of all the diverse relationships that exist – or do not exist – between the component parts of the big picture. Visualized and dealt with this way, culture and cultures provide the context, container, and perspective that is necessary to see and come to grips with the major imbalances and disharmonies that exist in the world today, such as the relationship between people and the natural environment, the material and non-material dimensions of development and life, the arts and the sciences, human rights and human responsibilities, different races and genders, technology and society, rich and poor people and rich and poor countries, the self and the other, unity and diversity, and many others.

Many of these present imbalances and disharmonies are having devastating effects and consequences at this troublesome time due to colossal swings in the pendulums of power, such as the one between the arts and the sciences which has resulted in deep and painful cuts in funding for myriad artistic, humanistic, and heritage activities, programs, courses, organizations, artists, and teachers over the last few decades while simultaneously facilitating huge increases in the funding of scientific activities, projects, courses, organizations, scientists, and educators. While addressing and overcoming severe imbalances and disharmonies like this and many others will not be easy, clearly the most essential step that can be taken at the present time is seeing relationships in holistic and harmonious rather partial, polarized, and disharmonious terms. As a result, what partialism, specialization, polarization, division, and separation are and have been to the past and the present, holism, the holistic perspective, harmony, and unity must be to the future. This does not mean that economic needs and activities must be downplayed or ignored. On the contrary, they may even be more important and enriched more fully in the future because they will be seen from a substantially broader, deeper, and more fundamental perspective, situated more effectively in the right environmental, human, and cultural context, and dealt with in a more enlightened and responsible manner. (13)

There is another benefit from this that should also be taken into account and utilized fully rather than pushed aside and ignored. It is the fact that when culture and cultures are seen and defined as complex wholes and total ways of life, it is possible to bring things

together rather than split them apart – “to unite rather than divide” – because this is what creating wholes and total ways of life from many different parts is really all about, designed to accomplish, and urgently needed at this time. This is especially important going forward into the future because we have become remarkably skilled at breaking wholes up into many parts through specialization, while, at the same time, have lost our capacity for connecting the parts together to create wholes, thereby explaining the enormous amount of polarization that exists in the world and the need to rectify it in the future.

In order to realize these benefits and capitalize on these opportunities, it is necessary to create a “new narrative” by using a different terminology as well as more appropriate wording and ideas to create and describe this narrative. Nowhere is this more important than in shifting from words and ideas like “development” that is concerned primarily with developing economies, industries, economic systems, and so forth that are parts of something much larger and more fundamental, to words like “cultivation” that are concerned with activities such as cultures as complex wholes and ways of life and therefore such words as “cultivating,” “harmonizing,” and “balancing” that are essential if cultures in the holistic sense are to evolve properly and function effectively in the years ahead.

This new narrative and wording is consistent with the thoughts of such scholars as Marcus Cicero, the great Roman orator and statesman who defined culture formally for the first time in history more than two thousand years ago as “the philosophy or cultivation of the soul” because it is derived from the Latin verb “colere” meaning “to cultivate,” as well as Voltaire, who was also a strong advocate for culture and rhetorically asked himself this question several centuries ago, “Do I plant, do I build, do I “cultivate?” This was necessary because a great deal of cultivation, harmonization, and balance is needed in this remarkably organic, fluid, dynamic, and all-encompassing process. This terminology is far more consistent with activities like cultivating crops and gardens than developing machines, industries, systems, or computers that are far more inorganic, mechanical, and quantitative.

Just as there are many different types of machines, industries, systems, computers, and so on in the domain of economics, so there are many different types of gardens in the realm of culture in general and horticulture, silviculture, and permaculture in particular.

Speaking generally, there are two basic types of gardens. The first type are gardens that are composed of the same flowers, such as tulips and tulip gardens in the Netherlands and roses and rose gardens in England. These gardens are very beautiful when they are in full bloom and cultivated and harmonized effectively by arranging the plants and flowers properly and removing all the weeds which is also a very essential part of gardening. Gardens like this are very similar to “unicultures” in the human realm because most people

are much the same or similar because they come from identical ethnic stocks and similar backgrounds. The second type are gardens composed of many different flowers, which is much more common. This type is very similar to “multicultures” in the human domain because they are composed of many different kinds of people from very different ethnic stocks and backgrounds. However, regardless of the type, gardens require a great deal of cultivating, harmonizing, weeding, and pruning if they are to grow, function, and be displayed properly. Added to this are many other types of gardens that can also be extremely beautiful when they are cultivated and cared for effectively, such as English country gardens and Japanese gardens. In this latter case, every leaf, flower, rock, shrub, or pool of water is situated in just the right place in order to achieve the best effect and open the doors to experiences such as tranquility, spirituality, stillness, and silence.

This makes gardens and their cultivation perfect symbols and ideal metaphors for thinking about and cultivating cultures. (14) This is because the focus is on the whole (cultures) and not just a part or parts of the whole (economics, technology, science, and so forth) as well as harmonizing all the diverse parts to achieve just the right effect.

III SHIFTING TO CULTIVATING CULTURES

This horticultural example illustrates why it is so imperative at this crucial juncture in history to make the transition from developing economies – important as this is, has been in the past, and will be in the future – to cultivating cultures as the most effective way to go in the years, decades, and possibly centuries ahead. For just as many factors and the beliefs of numerous practitioners and economists such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, Alfred Marshall, John Maynard Keynes, and many others played a foundational and transformative role in the development of economies and creating the economic age we are living in today, so many factors and the beliefs of numerous practitioners and cultural scholars such as Jacob Burckhardt, Franz Boas, Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, Alfred Kroeber, Pitirim Sorokin, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Thomas Berry, Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and many others should play a seminal role in the cultivation of cultures and opening the doors to a cultural age in the future. (15)

There is a reason for this. Developing economies is largely a highly specialized, focused, partial, and one-stage activity based on creating goods, services, and material and momentary wealth by breaking wholes up into parts, specializing on very specific production functions, and relying on markets and the marketplace to solve most if not all the problems that arise from this. In contrast, cultivating cultures is a far broader, deeper, holistic, and two-stage activity predicated on creating well-being in all its diverse forms and manifestations, but also, and equally as important if not more important, achieving

harmony, balance, and synergy between all the different parts of cultures, much like cultivating beautiful gardens. This is because cultures as wholes and overall ways of life are much greater than the parts and the sum of their parts because new qualities and capabilities are brought into existence when these wholes and ways of life are created that are not in the parts taken separately or by themselves.

In order to achieve this much more vaulted, value-laden, all-embracing, and harmonious state of affairs, economics and economies in the partial, specialized, and one- dimensional sense will have to be seen and dealt with in the future as essential components of culture and cultures in the holistic and two-dimensional sense. It follows from this that the challenge of the future is not to downplay the importance of economics and developing economies in the overall scheme of things, but rather to incorporate and position economics and economies properly in the substantially broader, deeper, and more quintessential realm of culture and cultivating cultures. As a result, what partialism, the partial perspective, and wealth are to the world of the present, holism, the holistic perspective, and well-being must be to the world of the future.

Just as developing economies and living in an economic age has its practical objectives and theoretical ideals, so does cultivating cultures and entering a cultural age. Included among the practical objective are: seeing and dealing with the big picture of the world rather than a specific or essential part of it; enhancing and harmonizing community, town, city, regional, national, and international cultures in holistic terms; treating humans as people and citizens of countries rather than consumers of products and maximizers of their satisfaction in the marketplace; companies earning reasonable rather than excessive or maximum profits; policies based on the needs and interests of all people, countries, and cultures and not just wealthy elites, powerful corporations, and privileged economies; and people, corporations, and governments making decisions and being responsible for them rather than relying on the marketplace and markets to make most of the decisions for them. As far as ideals are concerned, included here among others are: striving for inclusion, equality, order, stability, and security; placing a high priority on creativity, diversity, unity, and excellence; pursuing joy, happiness, justice, beauty, and truth; valuing freedom, democracy, and peace; respecting the needs, rights, values, identity, lifestyles, and ways of life of other people and countries; and manifesting compassion, empathy, and forgiveness whenever and wherever possible. These practical objectives and theoretical ideals should be constantly borne in mind and pushed to the forefront when cultures are being cultivated.

In order to be successful in cultivating cultures in holistic terms, it will be necessary to create a set of comprehensive cultural indicators that is consistent with these practical

requirements and theoretical ideals. These indicators will have to provide more expansive, effective, and specific ways of evaluating the state of cultures in the all-encompassing sense and improving people’s, countries,’ and the world’s well-being much more effectively than the present economic indicators, which are confined largely to gross or net national product, per capita income, rate of economic growth, and a few others more recently. These are still the principal indicators that virtually all countries, governments, and people use today, despite concerted attempts by the United Nations and many other international organizations to add other important indicators such as education, health care, and longevity, and, in the case of Bhutan, “gross national happiness.” This indicator is seen by some to be a substantial improvement on the economic indicators. However, it is not used by most people, countries, and governments at present because happiness is a difficult concept or feeling to pin down, experience, define, and measure.

Shifting attention from economic wealth to cultural well-being is the key to creating and utilizing this greatly expanded set of cultural indicators. In the creation of these indicators, four matters stand out above all the rest. First, these indicators must come from a much broader range of disciplines, sources, and policy areas, as well as capable of being combined and prioritized. Second, the best indicators in each area will have to be selected for inclusion in the final set of indicators. Third, the final indicators will have to be refined over time in order to improve their effectiveness, coverage, and applicability. And finally, the resultant indicators will have to be consistent with the nature and relevance of the problems and needs that exist in the world at this time and going forward into the future.

While it will take time to develop and refine this set of cultural indicators, fortunately many of the most important ones already exist and only need to be pulled together and refined rather than developed from scratch. Included among these indicators are: environmental indicators such as the state and rate of climate change and global warming, the quantity and quality of natural resources such as fresh water and clean air, as well as the level and amount of toxicity, pollution, and waste; economic indicators, such as the overall standard of living of people and countries, income and employment rates, and future prospects and possibilities; health indicators, such as longevity, the availability of health care services, medical facilities, and hospitals, disease control and prevention sites, and recovery rates from substance abuse and other debilitating diseases; social indicators, such as participation rates and levels in community, regional, national, and international affairs, the state and provision of safety and security measures as well as rates of crime, violence, and hate; artistic, political, spiritual, and scientific indicators such as the quantity and quality of artistic, governmental, and scientific offerings, services, facilities, and organizations, the stability of these institutions and systems, the diversity of

religions and spiritual options, and the availability of scientific and technological techniques and digital devices; educational indicators such as student-to-teacher ratios, access to excellent elementary, secondary, and post-secondary education for all genders, races, and income groups, student achievement and drop-out rates as well as debt loads and deficits, and the availability of qualitied teachers and life-long learning possibilities; and recreational indicators, such as the availability of different types of sports, parks, and conservation areas, walking and hiking trails, and other pursuits and facilities. Development of this set of cultural indicators will require a great deal of collaboration, consultation, and compromise, as well as monitoring and enforcement because many of these indicators already exist but are not taken seriously compared to the economic ones.

In the creation, utilization, and enforcement of these indicators, much more attention and a far higher priority will have to be given to the state of the natural environment; the relationship between people and the natural world; the well-being of other species and not just the human species, and the many different ways cultures can and should be cultivated in the years and decades ahead. If this is achieved, it will result in more inclusion and less exclusion; horizontal and “ground up” and not only vertical and “top down” cultivation of cultures at all geographical levels; favouring conservation, preservation, and distribution over excessive consumption, production, and materialism; focusing on unity rather than division, peace rather than war; caring and sharing rather than greed, self-centredness, and aggression; beauty over brutality; and more funding for the arts, humanities, and heritage activities in order to bring them into line and equilibrium with the sciences, artificial intelligence (AI), and contemporary technology.

Concern for these matters brings us to the second step in this two-stage cultivation process. It is coming to grips with the destructive disharmonies and polarities that exist between many key activities and forces in the world and the dire need to create harmonious relationships between them in the future. While this second step does not exist in developing economies because problems like this are expected to be self-correcting or dealt with by the marketplace if they get out of hand, this is a crucial step in cultivating cultures because countervailing measures and corrective mechanisms will have to be created and put in place wherever and whenever these difficulties exist and manifest themselves in the world. Many cultural scholars and historians have expressed the need for this, such as Eleonora Barbieri Masini who said, “culture in the future is the crux of the future,” Jean d’Ormesson who observed, “Culture used to look backward in order to understand the world; now, all of a sudden, it is looking forward in order to change it,” and Johan Huizinga who put his finger on this entire matter when he said:

The realities of economic life, of power, of technology, of everything conducive to man’s (humanity’s) material well-being must be balanced by strongly developed spiritual, intellectual, moral, and aesthetic values. The balance exists above all in the fact that each of the various cultural activities enjoys as vital a function as is possible in the context of the whole. If such harmony of cultural functions is present, it will reveal itself as order, strong structure, style, and rhythmic life of the society in question. (16)

Addressing this specific challenge and achieving it in practical terms will not be possible without harmonizing the severe disharmonies that exist between the arts, humanities, and heritage of history and the physical, natural, social, and human sciences because they underlie and influence so many other activities in life and the world. This disharmony exists because the sciences are deemed to be part of the economic base and therefore the basics in life, whereas the arts, humanities, and heritage of history are deemed to be part of the non-economic superstructure and consequently the frills in life.

This severe disharmony needs to be rectified without delay by increasing the priority and funding for the arts, humanities, and heritage of history considerably so they are in harmony and balance with the sciences. (17) This is imperative because the world has become a very inhumane and impersonal place in recent years due to these and other imbalances and disharmonies that are often devoid of feelings, emotions, compassion, forgiveness, kindness, and ethical conduct. How could it be otherwise when artistic, humanistic, and heritage activities have been cut so drastically in countless educational institutions, societies, and countries in the world? Only a profound change in this area and harmonization of these diverse activities will correct this highly polarized situation. As Toni Morrison, American author and Nobel Prize winner for Literature in 1993, put it:

This is precisely the time when artists go to work… There is no time for despair; no place for self-pity; no need for science; no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. This is how civilizations heal. (18)

This is desperately needed at present because the arts, humanities, and heritage of history are not only valuable in their own right as ends in themselves that are capable of bringing a great deal of happiness, joy, beauty, and reflection into people’s and countries’ lives as well as the world at large, but also means to other ends that contribute significantly to major improvements in people’s overall health and well-being, make valuable contributions to economic growth and developing economies, facilitate countless social

interactions, exchanges, and connections between people, groups, and organizations, celebrate essential civic events and political occasions such as the creation of countries’ constitutions, national holidays, flags, and anthems, reduce the huge ecological footprints we are making on the natural environment, and many others. And this isn’t all. They also provide the signs, symbols, myths, legends, metaphors, rituals, and so forth that are necessary to comprehend culture in holistic terms, cultivate cultures in the all- encompassing sense, and open the doors to a cultural age.

We need to take advantage of these multifarious benefits and profuse opportunities if we are to be successful in producing and experiencing more peace, order, stability, sustainability, and harmony in the world, less consumption, pollution, environmental devastation, and waste, wars over land, resources, and control over strategic territories in particular locations in the world, conflict between different genders, classes, tribes, races, peoples, countries, and many others. While the sciences, AI, and other technologies have a very important role to play in this, so do the arts, humanities, and heritage of history. In fact, they have a more seminal and fundamental role to play at this specific time by bringing more humanity, humility, generosity, and kindness into the world and making the world a more humane place for all people and all countries.

These are not the only reasons why the major disharmony that exists between the arts, humanities, heritage of history, and the sciences needs to be corrected and terminated. It is also required to make a substantial contribution to reducing the huge impact we are having on nature and other species. This is because many artistic, humanistic, and heritage activities are much more “labour intensive” than “material intensive,” as well as create “fulfilling experiences” rather than “physical products.” Think about it for a moment. Much less damage is done to the natural environment and utilizing scarce resources when people are sitting in a concert hall or a comfortable chair in their living room listening to music, watching a theatrical or dance performance at the local arts facility, or painting pictures rather than buying another car to put in the driveway to impress their neighbours.

Conservation and sustainability achievements like this won’t happen without addressing the many other major imbalances, disharmonies, divisions, and polarizations that exist in the world today mentioned earlier. Nor will they happen without dealing with problems like these and others before or when they occur rather than after they happen and it is too late to do anything about them and they multiply and escalate out of control. Developments like these, and others, are also needed to put humanity and the world in the strongest possible position to confront and come to grips with the world’s most dangerous

and debilitating problems going forward into the future. As Huizinga put it in terms of the disharmony that exists between people and the natural world:

A culture which no longer can integrate the diverse pursuits of men (people) into a whole, which cannot restrain men (people) through a guiding set of norms, has lost its center and has lost its style. It is threatened by the exuberant overgrowth of its separate components. It then needs a pruning knife, a human decision to focus once again on the essentials of culture and cut back the luxuriant but dispensable. (19)

Interestingly, rectification of the severe disharmony that exists between human beings and the natural environment doesn’t have to end with reducing the demands we are making on it, imperative as this is. We can do far more and much better than this, such as enhancing the state of the natural world beyond what it is today by seeing it from a cultural rather than economic perspective. Here is what Huizinga – who was deeply concerned about the state of the natural world all his life and a century earlier – had to say about enhancing the natural world and our roles and responsibilities in this:

A community is in a state of culture when the domination of nature in the material, moral, and spiritual realms permits a state of existence which is higher and better than the given natural conditions; and when this state of existence is furthermore characterized by a harmonious balance of material and spiritual values and is guided by an ideal … towards which the different activities of the community are directed. (20)

We have all seen and experienced many examples of this, especially ones connected to the arts to sustain the present preoccupation for a moment longer. Think, for example, of all the many artistic activities that take place outdoors in natural settings such as in deep forests or on lakes. I am thinking here of the Donauinselfest that is held in the middle of the Danube River in Austria, the Glastonbury festival in Pilton, England, the Osaka cherry blossom festival in Japan, the Orvieto festival in Italy, the Tanglewood music and light festivals held at Tanglewood and in Tanglewood Park in the Berkshire area of the United States, the Shakespearean Festival in Stratford, Canada, the remarkable castle strategically perched on the top of a steep hill overlooking Lake Bled in Slovenia as well as the historical Church – Our Lady of the Lake – situated on an island in the middle of this lake, dance performances beside gushing rivers and bubbling brooks, music in parks and conservation areas, and the list goes on and on. Not only do these festivities, productions, and events

provide aesthetic experiences and “highs” that enhance and enrich natural settings and local surroundings that are extremely beautiful to begin with, but also they create spiritual, reverential, and ethereal states of being that are more than the natural features themselves. What a great objective this would be for humanity in the future; not only in terms of helping to overcome climate change, global warming, and the environmental crisis, but also enhancing and enriching the beauty of nature and the natural world beyond what it is today.

It is clear from this that many states of existence can be created and cultivated in the world of the future that are “higher and better than the given natural conditions.” In fact, the potential exists here to experience a real “paradise on earth” through all the actual and potential activities and devices that are now available to people and countries and can be used to expand and consolidate their knowledge and understanding of all the fascinating and diverse cultures in the world and cultivating them more effectively in the future. This is a very exciting process and worthwhile opportunity because it is capable of bringing an immense amount of fulfillment, satisfaction, and inspiration into our lives.

This is what makes learning as much as possible about culture and the diverse cultures in the world as complex wholes and total ways of life a categorical imperative in the future. This is because all the signs, symbols, technologies, AI and digital devices, creative works, and materials that are needed to achieve this holistic capability already exist and manifest themselves in some of culture’s most essential, exciting, and compelling activities. This includes beautiful music, exquisite paintings, precious craft objects, superb plays, enticing architectural creations, captivating historic monuments and sites, enchanting stories, savory cuisines, admirable humanistic deeds, and many others. These are the gateways that are needed to open the doors to this paradise on earth if we invest the time and make the effort to have in-depth encounters and experiences with them.

One cultural scholar who has delved deeply into experiencing this paradise of earth by exploring, studying, learning from, and cultivating the different cultures of the world is Brian Holihan. Over the course of his life, he has travelled to many different parts and places in the world to experience countless cultures first-hand, on the ground, and in depth. He has also studied cultures’ remarkable characteristics, patterns, symbols, themes, and achievements in considerable detail though his intensive research and writings. Learning about cultivating cultures in the holistic sense and expanding our knowledge, understanding, consciousness, and appreciation of them is what makes this paradise possible. Brian has made the case for this in his book Thinking in a New Light: How to Boost Your Creativity and Live More Fully by Exploring World Cultures. In Chapter 13 of this book, Brian sets out a very effective way to broaden, deepen, and connect with this

paradise by “looking at, with, and beyond cultures,” or what he calls “the AWB circle.”

(21) An additional advantage of this book is that he illustrates and applies this technique to many cultures in Southeast Asia that are rapidly gaining prominence and generating a great deal of interest, appreciation, and appeal in the world.

IV THE NECESSITY OF CULTIVATNG CULTURES IN PRACTICAL TERMS

We are not as far from realizing the transition from developing economies to cultivating cultures in factual terms as we might think. While many new values, lifestyles, and ways of life will have to be created to come to grips with the dangerous problems that exist in the world today, as we have seen, many of the practical objectives, theoretical ideals, most essential cultural activities, and creative capabilities that are needed for this already exist and are waiting to be adopted, utilized, and applied. What is most imperative now, however, is to shift our perceptions and perspectives from a very essential part of the whole (economies) to wholes (cultures); address disharmonized cultural relationships; accord a high priority to cultivating cultures as the most essential requirement going forward into the future; and stand up and be counted on matters like this and others when this is required. In order to do this, leadership and proactive initiatives will have to come from four main groups or stakeholders: the arts and cultural communities in the world, corporations and organizations, governments and politicians, and the public at large.

As we have seen, developing economies has been driven primarily by economists, corporations, financial institutions, wealthy elites, skilled labourers, aggressive capitalists, countless inventions, and clever politicians and diplomats. They have been able to take advantage of such potent factors as specialization, huge concentrations of capital, numerous natural resources, myriad mechanical inventions, millions of companies and factories, and creating countess products. The arts, humanities, heritage of history, culture, and many other activities like this have been grossly undervalued and marginalized in this powerful process because they are seen as frills, leisure-time activities, and their economic contributions are deemed to be “quite small.” This caused Oscar Wilde to quip sarcastically a long time ago that, “it is possible to know the price of everything and value of nothing.”

Unfortunately, he was right. I say “unfortunately’ because undervaluing and marginalizing the arts, humanities, heritage of history, culture, and related activities has been a disastrous mistake in the economic age and still is today. When we look at these areas and activities from a holistic, chronological, and cultural perspective rather than partial, contemporary, and economic perspective, think of how valuable museums, art galleries, churches, mosques, temples, libraries, arts and cultural centres, symphony orchestras, theatre and dance companies, and all the precious works provided by them have

been to the revival of Europe and European countries from the end of the Second World War to the present day.

Trillions of dollars have been spent on these activities since the end of this disastrous war in 1945 and are still producing colossal monetary and financial benefits today as a result of all the funds that have been spent on them by Europeans as well as countless tourists who are pouring billions more into all European countries to enjoy their precious cultural treasures and priceless assets in this area. This is because these treasures and assets have deep cultural significance and resonate strongly not only with the millions of people who live in Europe today, but also the millions of others who travel to this part of the world because they say so much about these countries, the lives of the people who live there, and what their cultures are really all about. And what is true for Europe and European countries is also true for all other regions and countries in the world today.

Let’s take a more specific step in this direction to confirm this. Think, for instance, of what Johann Strauss II’s Vienna Waltz and The Beautiful Blue Danube mean to Austria and Austrian culture, Smetana’s Ma Vlast (My Country) and Vltava (The Moldau) mean to Czechia and Czech culture, Jean Sibelius’s Finlandia means to Finland and Finnish culture, Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance No. 1 (Land of Hope and Glory) and Handel’s Zadoc the Priest mean to England and English culture, Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote to Spain and Spanish culture, Claude Monet’s Lily Pond and Notre Dame Cathedral to France and French culture, and, going further afield in geographical terms, what Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird means to Americans and American culture, the Whirling Dervishes to Turks and Turkish culture, Machu Pichu to Peruvians and Peruvian culture, Confucius’ Analects to Chinese and Chinese culture, and countless others.

And this is not all. When countries are at peace, it is easy for people and countries to take their music, stories, dances, architectural masterpieces, historical monuments and sites, flags, anthems, humanistic deeds, and so forth for granted. However, when they are under siege, at war, and invaders are bombing their precious cultural assets to bits, there is usually a sudden realization of how priceless and incredibly important these assets really are, and quite possibly, the most essential of all for citizens, countries, and cultures. This is because they have a great deal to do with feelings of national identity, belonging, and pride, what is in their hearts, minds, souls, spirits, and deeds, their overall health and well- being, educating young people and future generations in their most cherished values, lifestyles, ideals, and ways of life, what they say about their cultures, the contributions made by past generations and current citizens to their countries, and how essential it is to preserve, protect, and keep them safe and intact.

This is why making a quantum leap in funding for these precious artistic and humanistic assets, cultural treasures, and many others for all countries is so essential. Not only is this necessary to capitalize on their remarkable value and importance in the overall scheme of things, but also to create more humanity, compassion, kindness, and spirituality in all countries and the world as a whole in the years ahead.

This is what makes people working in the arts, humanities, heritage, and such other cultural fields as anthropology, sociology, cultural studies, psychology, ecology, biology, botany, and zoology, as well as all their myriad organizations and departments, so valuable and timely. These are the people, disciplines, organizations, departments, and fields that are most familiar with and knowledgeable about culture and cultures as wholes and ways of life, how they function, and what they are designed to accomplish.

There are many ways individuals and institutions working in these areas and fields can fulfill their roles and responsibilities most effectively going forward into the future. They can, for instance, create the artistic and humanistic works as well as the academic courses, programs, and resources that are needed to broaden, deepen, and intensify people’s personal and collective knowledge, understanding, and consciousness of the intricacies, complexities, and essence of culture and cultures. They can also enhance awareness of the similarities and differences between all the diverse cultures and civilizations in the world, as well as the cultures of other species. And there is more. They can also create holistic portraits, maps, and culturescapes of their own cultures and how they can be cultivated most effectively in the future, as well as promote appreciation and use of the natural and cultural heritages of their own people and countries as well as the entire natural and cultural heritage of humankind. Furthermore, they can facilitate the enhancement and use of all the different communications vehicles and media capabilities that are available to celebrate the best in human nature, conduct, and character, contribute to reducing conflict, racism, and terrorism in the world, and create deeper and more interpersonal, interorganizational, and intergenerational bonds and relationships among people. While many resources already exist in most of these areas, what is needed now – and needed more than ever – is to take a much more systematic, integrated, and comprehensive approach to producing, utilizing, and sharing these materials and activities, as well as extending them well beyond certain groups and making them accessible to all.

This group can also activate and foster many more interactions, interconnections, exchanges, and agreements between the diverse peoples, countries, civilizations, and cultures of the world. This is especially important with respect to countries, civilizations, and cultures that are experiencing major conflicts, open hostilities, festering animosities, or engaged in conflicts and wars. Initiatives and activities such as these are desperately

needed at this time to pave the way for grossly improved intercultural, multicultural, and international relations, as well as to promote greater cultural sensitivity and acceptance of the diverse peoples, countries, cultures, and species in the world. They can also spread the word that it is time to enter a cultural age, explain why this is so important, and suggest what this age can and could be like using their own activities and experiences in the arts and cultural fields as guides, illustrations, symbols, and archetypes. This is required to move culture and cultures in general – and cultural cultivation and policy in particular – out of the margins and into the mainstream of modern life in all parts of the world.

This is why people and organizations working in these different fields have the most essential role to play and responsibilities to assume in making the transition from developing economies to cultivating cultures a success. While this group is spread across many areas and disciplines today, what is urgently needed at this time is to coalesce this group into a coherent, cogent, and potent community. If this group doesn’t provide the proactive leadership and transition skills that are necessary for this, cultivating cultures in the holistic sense will not happen and entering a cultural age will not become a reality.

A similar challenge faced people and organizations working in the environmental field half a century ago. They were also spread across many disciplines, activities, and areas that had to be brought together and coalesced into the aggressive and relentless environmental community and powerful movement they are today. They did this through the commitment of many dedicated environmentalists and ecological leaders, scholars, policy makers, and activists, as well as numerous institutions that represent these people and this field throughout the world at present. This is what is most needed in the cultural field today. A strong and vocal cultural community needs to be created that is capable of making culture and cultures the centrepiece of the world system and principal preoccupation of municipal, regional, national, and international affairs in the years ahead.

While people and organizations in the arts, humanities, heritage of history, and cultural fields have the most proactive and immediate role to play in bringing the cultivation of cultures to fruition and enabling them to flourish, many other people and organizations are not far behind. The driving force here is coming from corporations that are beginning to see themselves as cultural wholes in organizational and holistic terms, as proposed by such people as John Kotter and his theory of organizational leadership, Elliott Jacques and his concept of “corporate cultures,” Edward Schein and his book Organizational Culture and Leadership, (22) and especially Jerry Wagner, founder of Culture Quest and more recently Cultures in Action that advocates for the continuous improvement of tools, methods, and concepts such as company and team core values that enable the creation of positive and thriving workplace cultures. While this organizational

movement is still confined largely to corporations at present, this could prove to be a very beneficial and timely development in the future by extending it to many other types of organizations in the private sector and the public sector that are starting to accept and engage in this rapidly growing trend throughout the world as well.

In essence, this movement is focused on seeing organizations in cultural and holistic rather than corporate, organizational, and partial terms in response to such commonly heard phrases as “change the culture” and “systemic cultural change.” In practical terms, this means examining corporations and other organizations with respect to their original foundations and roots, underlying axioms and assumptions, and basic worldviews and value systems, as well as the way they treat their employees, customers, and the public at large, plan their future developments, and fit into the world in broader and deeper environmental, motivational, visionary, social, and human terms. In the case of corporations, hopefully this will result in giving up their commitment to maximizing their profits – which is proving to be very inhumane and unjust because it is compounding the colossal disparities and inequalities that exist in income and wealth throughout the world – and settling for reasonable or realistic profits, becoming much more committed to reducing their environmental impact (some are already doing this), as well as more engaged in the health and well-being of their communities, generous in their financial donations, active in their social engagements and humanistic endeavours, and committed to cultivating cultures and entering a cultural age in the future.

And this brings us to governments and politicians as quite possibly the most important group of all in cultivating cultures as their most important priority. In order to achieve this, it will be necessary to understand why developing economies is no longer working and why it is so essential to set their sights on cultivating cultures in the broader, deeper, and more quintessential environmental, humanistic, and cultural sense. As indicated earlier, this means incorporating economies in this far more all-encompassing context in order to strength the commitment that is made to reducing climate change, global warming, and the pressure on nature and nature’s resources, sharing income and wealth far more equally and fairly through progressive taxations measures, realizing greater inclusion and less exclusion, rectifying the severe disharmony that exists between the arts and the sciences, and many others.

There is a compelling reason for this. It is because politics and governments and culture and cultures share one very powerful idea and ideal in common that is of utmost and crucial importance to the world of the future. It is commitment to seeing and doing things in holistic rather than partial terms, and therefore taking the needs of all people, companies, and organizations and not just wealthy elites and powerful corporations into

account in their future decision-making processes and policy practices. If this is not done by governments and politicians, it will not be done at all because most people and organizations are engaged in looking after their own needs and interests and not those that have to do with other people, societies, countries, and cultures in holistic terms.

Unfortunately, no country or government in the world can claim that their national culture in this all-encompassing sense constitutes their central foundation and principal preoccupation in theoretical and practical terms. However, there are several countries and their politicians and governments that are moving steadily and progressively in this direction. The most obvious one is Indonesia. In 2017, the Indonesian government passed National Law No. 5 on Cultural Advancement that includes several key articles that place culture at the forefront of their country’s present and future development. This law states:

[The] Principles for the Advancement for National Culture of Indonesia are tolerance, diversity, cross-regional participation, benefits, sustainability, freedom of expression, cohesiveness, equality, and mutual cooperation. As for the purpose, it is to develop the noble values of the nation’s culture, enrich cultural diversity, strengthen national identity, strengthen the unity and integrity of the nation, educate life for the nation, improve the image of the nation, realize civil society, improve the welfare of free people, preserve the nation’s cultural heritage, and influence the direction of development so that Culture becomes the national development direction.

While little is known about this law and legislation in other parts of the world at present, this development is not surprising in view of the fact that Indonesia has had some of the world’s most important cultural scholars and journalists over the last fifty years. Most notable in this regard are: Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana, author of such books as Socio- Cultural Creativity in the Converging and Restructuring Process of the New Emerging World and Values as Integrating Forces in Personality, Society and Culture; Soedjatmoko, former rector of the United Nations University in Japan and a well-known international diplomat, cultural scholar, and historian with several publications to his credit including Economic Development as a Cultural Problem, An Introduction to Indonesian Historiography, and, co-edited with Kenneth W. Thompson, Culture, Development, and Democracy: The Role of the Intellectual – A Tribute; Mochtar Lubis, a courageous journalist, media founder, and prolific novelist who was jailed a number of times for his opposition to various political parties and regimes in Indonesia and is the author of Twilight in Jakarta and many other novels; and, most recently, Mira Sartika, cultural geneticist, founder, and director of the Chakra Cultural Foundation and its Center for Cultural Studies, and author of The Map of Civilization: A Geocultural Synthesis, Cultural Genetics, and

Culture in Sustainable Development: Harmony through Differences. (23) Also not surprising in this respect is the fact that one of Indonesia’s most cultivated, cherished, and distinctive cultural regions – there are many – is Bali, which is well known internationally for the high level of its creativity and numerous artistic and cultural accomplishments, as well as one of the most coveted tourist destinations in the world.

Indonesia is not the only country that is steadily and progressively moving toward the centrality of culture in holistic terms in general and its own national culture in particular. Others on the list would undoubtedly include Spain, Italy, France, and Japan. They deserve a great deal of attention and recognition for their incredible cultural achievements over many centuries and especially over the last century, as well as producing their fair share of cultural assets and scholars along the way.

People at large are the final and largest group of all. Their role and responsibility is to get deeply immersed in the process of cultivating their own cultures at the local, community, town, city, regional, or national level, experiencing the paradise on earth that comes from this and learning about other cultures, and creating the values, lifestyles, and ways of life that are needed to achieve this. In time, developments like this, and many others, will put all people, countries, and the world at large in the strongest possible position to confront and come to grips with the globe’s most life-threatening problems. Eventually, it should lead as well to realizing the priceless value of wholeness, oneness, togetherness, and unity in the world, as Robert Atkinson points out in his book A New Story of Wholeness: An Experiential Guide for Connecting the Human Family:

Unitive narratives are needed now more than ever to lead us through a process of shifting the focus from individual wellbeing to collective wellbeing. In our time, the part no longer takes precedent over the whole. Both are completely interdependent. Exclusive emphasis upon any one part endangers the whole. (24)

This is becoming clear and much more realistic today through the great cultural awakening that is taking place in the world. This awakening is manifesting itself in the remarkable insurgence that is occurring among myriad Black, Indigenous, colonized, and oppressed people, and many others who are connecting or reconnecting with their original cultures, worldviews, languages, customs, and ways of life. This is also the case for countless organizations as indicated earlier that are recreating their administrative and managerial structures in order to make them more inclusive, relevant, resilient, and humane, as well as many cultural scholars, historians, and practitioners who are doing much more research and writing about culture and all the diverse cultures in the world and countless artists who are developing many new, exciting, and innovative forms of cultural

expression, experience, and consciousness. (25) This is as it should be. For as John Cowper Powys observed many years ago, “The whole purpose and end of culture is a thrilling happiness of a particular sort – of the sort, in fact, that is caused by a response to life made by a harmony of the intellect, the imagination, and the senses.” (26)

Without doubt, culture in general and cultivating cultures in particular possess the potential that is necessary for all people and countries to live full, fulfilling, and constructive lives, create a great deal more kindness, happiness, well-being, humanity, and equality in the world, and make the world a better, safer, and more stable, comfortable, and peaceful place for all people, countries, species, and the world. Let’s get on with this.

REFERENCES

- For a detailed examination of how economics, economies, and the economic age were developed over the last two and a half centuries, see D. Paul Schafer, Revolution or Renaissance: Making the Transition from an Economic Age to a Cultural Age (Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa Press, 2008), Part I, The Age of Economics, pp. 9-135.

- Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (London: Wordsworth Editions, 2023).

- David Ricardo, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (London: Dover Publications, 2004).

- Karl Marx, Capital, 3 volumes (London: Hamondsworth: Penguin, 1976).

- M. M. Bober, Marx’s Interpretation of History (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1965).

- Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics (London and New York: MacMillan, 1920).

- Alfred Marshall, Theory of Economics, quote posted on the Internet (italics mine).

- John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

(London: Macmillan, and New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1936).

- Edward Burnett Tylor, The Origins of Culture (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1958),

p. 1, (italics and inserts mine).

- Ruth Benedict, Patterns of Culture (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963), p. 33 (italics mine).

- Ruth Benedict, ibid., p. 36.

- See interview with Thomas Legrand, author of Politics of Being, WISDOM and SCIENCE for a New Developmental Paradigm – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zB-phstirp4 – posted on the Home Page of the World Culture Project Website.

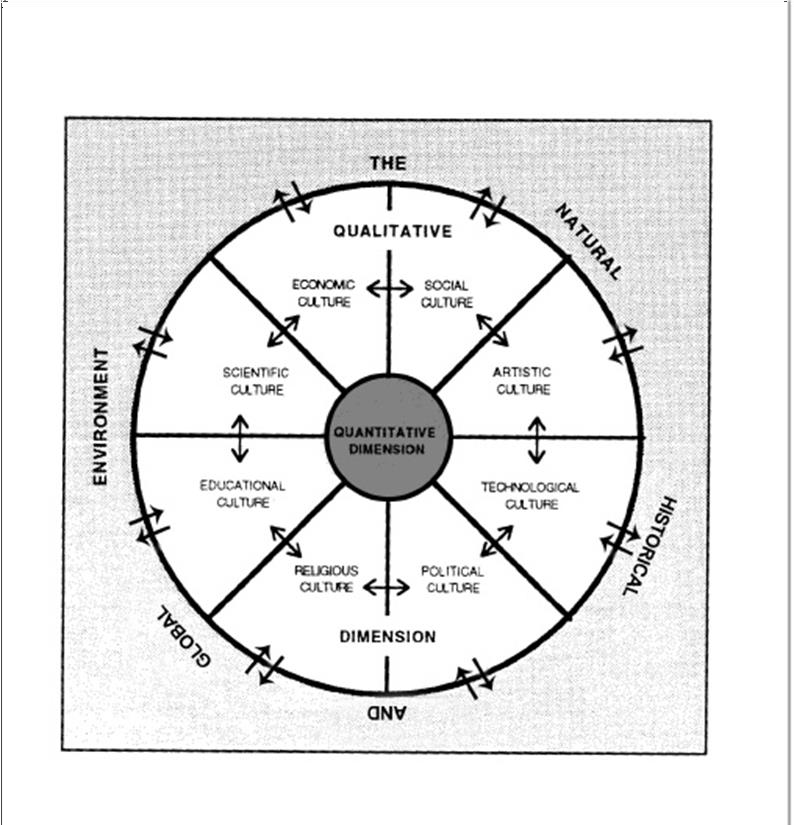

- In the diagram below, culture and cultures are depicted as wholes and total ways of life by the full circle made up of many different parts that all share culture in common. Depicted in the cricle are all the different parts or sectors of cultures, with the arrows going in both directions rather than one direction because this is the way they interact and function in the real world. This is also true for the way culture and cultures are situated in the natural, historical. and global environment in the vast space outside the circile and all the complex interactionss that go on between and among cultures and this substantially larger context, which is why the arrows are going in both directions and one in one direction as well.

THE HOLISTIC NATURE OF CULTURE AND CULTURES IN CONTEXT

- D. Paul Schafer, ‘Horticulture and Human Culture.’ Posted on the Hot Topics section of the World Culture Project Website at: www.worldcultureproject.org

- D. Paul Schafer, The World as Culture: Cultivation of the Soul to the Cosmic Whole (Oakville, ON: Rock’s Mills Press, 2022). This book traces the evolution of culture as an idea and reality over the course of human history and provides a great deal of information on the perceptions, definitions, and theories of cultural scholars and historians and the actions of cultural practitioners, as well as numerous quotes from their work and publications as well as a “timeline on the history of cultural thought” at the end of the book.