Gianmaria Ajani, DIST – Università e Politecnico di Torino

L’arte come espressione di tecnica, l’arte come manifestazione di sentimento: non è necessario essere un intenditore d’arte per evocare quanto sovente queste due descrizioni si siano opposte. Come si colloca tale tensione nei confronti di una nuova forma di “arte”, che emerge dall’impiego di tecnologia guidata dall’Intelligenza Artificiale ? Fin dagli anni ’70 i computer sono stati utilizzati per generare poesie, dipinti e composizioni musicali. La maggior parte di quelle opere fatte dagli input del programmatore, mentre la macchina interveniva semplicemente come strumento, non dissimile, nella funzione, da un pennello o un apparato fotografico. Oggi siamo di fronte a un cambiamento tecnologico che ci offre l’opportunità di rivalutare il ruolo svolto dalla tecnologia digitale nel processo creativo. Quando i computers erano considerati nient’altro che uno strumento, il regime giuridico delle opere così prodotte veniva applicato privilegiando comunque la presenza di un autore umano “dietro la macchina”. La maggior parte dei meccanismi odierni basati sull’intelligenza artificiale, diversamente, sviluppa algoritmi attraverso l’apprendimento automatico (machine learning). La progressiva autonomia delle macchine dagli esseri umani pone così una nuova sfida ad una serie consolidata di disposizioni di legge. E di fronte alle nuove sfide introdotte dalle opere generate dall’intelligenza artificiale, il diritto appare inadeguato.

—————-

Introduction.

Art as an expression of technique, art as a display of sentiment: there is no need to be an art specialist to evoke how often these two descriptions have been opposed. Today we observe new regulatory approaches arising from technology such as the emergent Artificial Intelligence (AI)-generated art. Since the 70s computers have been used to create imaginative works such as poetry, paintings, and musical compositions. Most of those computer-made oeuvres derived from the programmer’s inputs, while the machine was simply an instrument, like a brush or a camera. While this perception persists today, we are also facing a dramatic technological change which grants us the opportunity to re-evaluate the role played by processors in the creative course. When processors were considered as nothing more than a tool, legal provisions were applied accordingly. Most of today’s AI-driven mechanisms, however, develop algorithms through machine learning. The incremental separation of machines from humans brings a new challenge to an established set of provisions of law. And when confronted with new challenges brought in by AI-generated works, the law appears inadequate. Globally, most commentators refer to the letter of the law, where a “human factor” seems to be an inescapable requirement of copyright authorship. Others minimise the matter, noting the scarcity of judicial cases where AI-generated art is at stake.

In my opinion, the consideration of the impact of AI on copyright laws is significant and should not be postponed, based on a pretext of immaturity, if not irrelevance, of the topic. It is significant at least for the following reasons: AI-driven systems and the artworks that they produce nurture policy issues that affect copyright ownership entitlements and legal protection of artists, researchers, engineers who are experimenting in the field. Also, AI-generated creations question the dynamics among art producers, artworks, and the public. The aim of this essay is to indicate that this matter is incumbent and relevant for both international and national legal regimes of regulating art production.

Imagination, creativity, and artmaking are abilities peculiar to human intelligence, and vibrant marks of humankind. Among the three, imagination precedes creativity in the development of human consciousness, while creativity may, but not necessarily does, reflects itself in a product. A product can be a tool, a tale, and even, an artwork. Initially, the law paid little attention to such creativity. Indeed, both the production and trade of its results was regulated by two main areas of private law: property and contract. Eventually, creativity was perceived as an important driver of human progress. This perception led to the first copyright regimes being established in the 18th century.

Today, the development of machine learning and deep learning software allows autonomous systems to learn and execute outputs without being explicitly instructed by human beings. While arguing that the traditional copyright laws are inadequate to cope with new technology involved in creating artworks, Shlomit Yanisky-Ravid contends that oeuvres autonomously generated by machines challenge a basic tenet of copyright law, namely that only humans can create works: “Copyright laws are simply ill-equipped to accommodate this tech-revolution and are therefore unlikely to survive in their current form. To address the change in the way art is being created, we must either rethink these laws, give them new meaning, or be ready to replace them”.[1]

Clearly, AI-generated creations raise several copyright questions.

Firstly, the development outlined above has occurred in parallel with a continuous evolution of data mining technology. Further, widened access to all types of data also represents a set of multiple challenges to copyright regulations. Training an algorithm may require the use of images, texts, or other data. Artworks used to train can be in open source, in the public domain, or protected. While it would not be easy to determine which works have been effectively used in the training process, one wonders whether a claim for copyright infringement of protected works would be successful.

Secondly, the programmer could sell the algorithm’s code as a work in itself.

Thirdly, from a different, but altogether relevant, perspective, AI-generated art raises the issue of preserving algorithms. Their fast deprecation has even encouraged some artists to qualify their output as temporary performances rather than paintings or videos.[2]

Fourthly, authorship is concerned whenever an AI system, being dependent on the learning algorithm, is capable of making combinations that are increasingly autonomous from the original set of materials provided by the programmer. When the deterministic nature of software becomes a probabilistic process, we observe a qualitative leap that cannot be explained by the metaphor of the “brush and tool”. All these issues have legal implications that are not clearly covered by current copyright regulations.

In this essay I explore the fourth issue, namely the ontological nature of AI-generated creations and the challenge they bring to classical copyright law concepts, such as authorship and originality.

AI-generated art and creativity.

Today computers produce artistic or innovative outputs. These programs, however, should not be considered as either “able” or “not able” to autonomously produce works.[3] Rather, there is a continuum linking, at one extreme, ‘computer-assisted’ works and, at the other extreme, autonomously generated works. The middle of the continuum is broad and includes methods with varying grades of human intervention. Depending on the degree of human intervention, the form of the output may be minimally, significantly, or substantially determined by software. And while for computer-assisted works the software is a production device, for autonomously generated works the outcome may be unpredictable.[4]

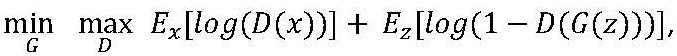

These outcomes become an epistemological case. Their legal status is uncertain and depends on our attitude towards the degree of autonomy from humans that machines “enjoy”. Already, we appreciate “e-David” and “Paul,” robots capable of drawing portraits in the inventive style of Patrick Tresset, their artist programmer.[5] More than merely copying machines, Tresset’s robots are fitted with an “autonomous artistic creativity” that makes them capable of producing “objects that are considered as artworks”.[6] Indeed those following contemporary art updates know that a “generative adversarial network” (GAN)[7], having referenced 15,000 portraits from various centuries, had painted on canvas a Portrait of Edmond Belamy.[8] The work, signed at the bottom right with

namely part of the algorithm code that produced it, was presented at a Christie’s auction.

The Paul-originated paintings have been exhibited in major art museums and acquired by galleries, museums, and art fairs for display, while the Edmond Belamy portrait was sold for 432.000 USD.

These examples, among others, evidence that questioning the nature of an artwork produced by automatic systems is not a pursuit confined within a purely theoretical debate. The existence of these works, and in particular, their appearance in the art world, forces us to understand their place within copyright regulation, as well as the art world.

Countless descriptions have been associated with the concept of “creativity”. It can be “weak” or “strong”, “exploratory” or “transformational”, and additionally, “4th dimensional”. A model of creativity devised by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi[9] includes three interrelated elements:

- an accepted, and agreed upon, domain of current knowledge;

- an agent who alters a component of the domain to produce something novel; and

- a field of experts that ultimately decide whether the novelty will be accepted into the existing domain.

Kyle Jennings has identified three criteria for an agent to qualify a system featuring creative autonomy:

- autonomous evaluation (the system can evaluate its acceptance of a creation without seeking opinions from an outside source); [10]

- autonomous change (the system initiates and guides variation to its standards without being explicitly directed when and how to do so); and

- non-randomness (the system’s evaluations and standard changes are not purely random).[11]

Applying these criteria to AI means that “[…] progress[ing] from a capable apprentice to a creator in its own right, an AI system must be able to both independently apply and independently change the standards it uses. This ideal will be called ‘creative autonomy,’ and represents the system’s freedom to pursue a course independent of its programmer’s or operator’s intentions”.[12] Following these approaches, an author is not the unique component of the creative process. Nor does creativity exist independently in any of the listed elements. Rather, creativity depends on individual capacity, acquisition of information and judgment by experts.

This perspective can free AI-systems from the identification of “autonomy” as a state of complete segregation. Kyle Jennings’ argument logically supports the recognition of a truly independent AI system as one where transformational (and not pure exploratory) creativity emerges out of interactions among many different agents. In such an environment, machine learning may enable an AI system to change its preferences not randomly, but as a reaction to continuously collected evaluations and opinions.[13] Also, an AI system may attain experience from the senses. For example AI painters have shown that AI paintings can be influenced by sounds, lights and temperature in the environment, or even keywords that the system autonomously chooses.[14]

In its purest appearance, creativity may lead to ingenious works which challenge standards and canons and ultimately produce unconventional art. “Unconventional” is the appropriate word as it means deviating from conventional canons. But is AI-generated art unconventional? Indeed, it is one thing to reproduce a painting from the digestion of thousands of similar artworks, and it is another to produce unusual works, marked by a new style.

Ahmed Elgammal, director of the Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Rutgers University, built upon the development of GAN systems to establish the creative adversarial network (CAN).[15] This system is specifically programmed to produce originality and creates images which differ from those collected. In this case, the images consisted of paintings from the 14th century onwards in all styles. Generally, works produced through a CAN system have received appreciation in the art world. Important auction houses in particular, have introduced these oeuvres into international visual art markets. CAN systems stretch across two extremes: the innovative capacity of AI-made works to depart from established canons, and the ability to produce oeuvres that are not foreseeable by the algorithm’s designer. One algorithm creates a solution, the other judges it, and the system loops back and forth until the intended result is reached. The innovative aspect is that the generator is informed to produce an image that the discriminator recognises as “art”, but which does not fall into any of the existing styles.

If humans do not trigger the action taken by an automatic system, nor partake at the end of the process by supplying sufficient “intellectual creation” to match the minimum standard of authorship requested by the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, one might well consider these outputs to be “autonomously computer-generated”.

“AI-made art” and the law.

Let us assume, then, that an oeuvre is produced via an independent AI process, free from human intervention in the making. What would its legal status be?

According to most authors, copyright law is not currently structured to accommodate the innovative authorship frame of “people-who-write-programs-that-make-art”.[16]

This position can be read in two different ways.

Firstly, whether innovative authorship leads to the recognition of authorship for programs-that make-art.

Secondly, whether a conservative approach would be adopted to maintain that copyright should only grant “human authorial rights”.

The latest generation of AI systems makes it difficult to understand where the programmer’s contribution ends, and the user’s role begins. This becomes even more puzzling when the program is coded to produce expressive choices independent of both the programmer and user. Indeed, perhaps the challenge AI brings to copyright law is so robust it necessitates a change of perspective regarding authorship requirements.

Such a change would undoubtedly challenge classic copyright law which focuses on the position of the author. Despite numerous position papers, white papers, governmental reports, and recommendations, national lawmakers have not yet addressed the subject. This is unsurprising as most policymakers view such regulation as premature. In their opinion, existing copyright laws can respond, at both national and international level, to the challenges brought into the system by AI-generated artworks.

In my view, this position holds so long as one maintains that artworks produced by machines are derived from human action. Until recently, it was a common belief that a machine, though defined as “intelligent”, lacked the “creative aptitude” to produce artworks. Indeed, itis well known that the law in many countries only protects “original” works created by human intelligence. “Until recently”, I said. However, today many new projects attest that it is not worth condemning the matter as simply irrelevant.

The 1886 Berne Convention failed to define authorship because it was commonly accepted that the term “author” always implies a human element. In the United States is more explicit as the Federal Copyright Office declared that it will “register an original work of authorship, provided that the work was created by a human being”.[17] This statement originates from the case Feist Publications vs. Rural Telephone Service Company Inc.[18]. In this case, the court ruled that copyright law only protects “the fruits of intellectual labour” that “are founded in the creative powers of the mind.”

Within the European Union, the Court of Justice has ruled several times that copyright only applies to original works, and that originality must reflect the “author’s own intellectual creation”.[19] Likewise, EU Member States national laws imply, more or less explicitly, that the “human factor” is the prerequisite to provide copyright protection to authors.

UK law deserves a special note, as its copyright legislation contains specific provisions dealing with computer-generated works. According to s. 178 of the UK Copyright Designs and Patent Act (CDPA, 1988), a computer-generated work is defined as “a work that is generated by a computer such that there is no human author”. Under s. 9.3 of the same CDPA authorship of such work is “given to the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”. However, this legislation is a legal fiction set to solve the authorship dilemma of AI works on the belief that the computer is merely a tool. Clearly, “the person responsible for making such arrangements is not the true author under copyright law, as evidenced by s. 9.1 CDPA”.[20] The more removed AI is from human interference, the less likely authorship will be granted due to the lack of human intervention. British and similar legislation adopted in other common law jurisdictions do not seem to be a workable solution to this dilemma. Even if it is viable for AI systems which are not autonomous, the identity of the “person responsible for the arrangements” remains unclear.

The problem arises when the automatically generated output cannot be traced back to any human action or interference. According to existent copyright regulations, an AI independently generated work will not be recognized as an “artwork” in the sense of copyright law and, therefore, will not be subject to the legal protection provided by copyright privileges. In other words, so long as the process is recognised by the law as driven by a human agent and the result of a human mind, the law will be adapted to follow suit and grant humans copyright. However, when technology advances to the extent that it is difficult to recognize the “person making the arrangements for the work”, there is a legal vacuum. The challenge cannot be solved by implementing minimal amendments to copyright law. Rather, we should understand that inertia or minimal adjustment will not make up for the uncertainties originated in the copyright systems by AI.

This vacuum will generate confusion and judicial irresolution.

In fact, the dilemma revolves around two options:

– a strict reading of copyright law: if there is no way to provide protection, then the law does not intend to protect AI generated works. This option will result in leaving AI generated artworks in the public domain,[21] or

– assigning the title and related protections by choosing one or more privileged holders such as the programmer [22] or the user.[23]

The “human factor”, then remains the centre of the analysis.

Its permanence, however, has not prevented a flourishing of proposals to find a way out of the maze of lacking legal regulations and outdated normative theories, to adjust copyright laws to the advancement of technology. Among those proposals the most challenging are the ones addressed to consider “AI-driven non-human agents” as potential subjects of law, as well as those developing new theories within the law of robots.[24] Colin Davies contends that “a corporate body has under UK law legal recognition as an individual.” Therefore, “a computer which is more akin to a true person, more particularly with the new generation of artificial intelligent computers, should be accorded the same status. This will enable us to attribute authorship of computer-generated works/inventions to the body best entitled to them, the computer, and allow the respective claims of interested parties to be determined not by arbitrary rules of law, but by the parties themselves, through negotiated contractual terms. Revolutionary this may be, but no more so than granting intellectual property rights, as we currently do, to a body corporate”.[25]

Advocating a legal status for intelligent machines, however, remains a proposal confined within a limited circle of proponents. The main counterargument is well known: the law acknowledges personality for corporations in all legal systems, but corporations are constituted by human beings. The traditional paradigm is based on the idea that humans are “behind” legal entities and corporations. This criticism still holds true at least for EU institutions. On 12 February 2019 the European Parliament adopted a Resolution on a comprehensive European industrial policy on artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics.[26] After describing AI as “one of the strategic technologies of the 21st century”, the European Parliament presented several recommendations to the Member States, advocating “human-centric technology,” to avoid the possible misuse of AI technologies to the detriment of fundamental human rights. The European Parliament insisted on the predominance of the human factor over computer systems based on “the ‘man operates machine’ principle of responsibility,” and recommend[ed] that “humans must always be ultimately responsible for decision-making”.[27]

As a set of Russian dolls, the human factor re-emerges from every notion, be it authorship, originality, or creativity. As the human factor is founded in classical copyright law, the latter influences any possible interpretation internal to the legal discourse. We must, therefore, accept that the legal interpretation is not ready to abandon its classical foundation. At the same time, we should also acknowledge that classical law is crippled by the advancement of new technologies, and in particular by the newly AI-autonomously generated oeuvres.

Conclusions.

Advancements in technology and the last generation of autonomous AI systems are posing a new challenge to the legal regime of authorship. Neither interpretation nor simple adjustments of existing laws seem to be a proper response. For the first time we experience a manner of making art which assumes the non-existence of a human author. Lacking an adequate understanding of the scale and perspectives of these advancements, it is likely that, while the art world is embracing AI-generated artworks, its legal counterpart remains unresponsive. This contribution aimed to offer a view on the phenomenon of AI-made art, and to observe how it can be accommodated within copyright law. I have distinguished between different kinds of AI-generated oeuvres. Most cases, to be precise, do not really challenge current laws. Whenever a human intervention can be detected in the creative process, an AI system remains a tool, a sophisticated tool, but a tool, nonetheless. And according to existing copyright laws, even a modest contribution is sufficient to recognize originality. An analogous solution applies whenever the artwork is independently created by the AI, but the human intervention consists in a selection of what has been made. In such cases the law is clear in recognizing human authorship as the act of selecting and choosing is traditionally viewed as subsisting of copyright. Beyond those instances, a remaining issue is whether a work autonomously generated and selected by an AI program, absent whatsoever human involvement, can subsist of copyright. In this case, different arguments lead to the conclusion that the current law is not helpful. Yet the lack of regulation does not necessarily mean that such works lack qualification as an artwork. It rather means there is an absence of legal protection. Rather than developing fragile legal fictions built on elements of company or copyright law designed with differing aims, the legal world should develop contractual models. Whenever the current law does not fit the needs of our human communities, contracts have proved to be the best adaptable, flexible, and specific remedy to gaps in legislation. Agreements could determine, case by case, how to allocate privileges and rights, and how to distinguish the contribution of every participant. Additionally, whenever human involvement is not detectable, contracts could grant legal significance to the inventiveness of the AI designers. Within Europe, scholars and experts, judicial courts, EU institutions have already begun adapting the law of contracts to resolve this lacuna. As a result, new areas of conventional relationships have been established, mostly based on agreed commitments to share rights, and allocate privileges, to increase information for the benefit of the parties and the general public. However, it is said that the art world does not warm to the idea of contracting as a remedy. This is certainly true. AI-generated art, however, occurs within a different environment, where know-how and financial investments in technology favour the recourse to voluntary agreements. Contracts and agreements among “non-authors” could provide some predictability while waiting for law to regulate the creative works produced by the art world.

[1] Yanisky-Ravid, Shlomit: “Generating Rembrandt: Artificial Intelligence, Copyright, and Accountability in the 3d Era. The Human-Like Authors Are Already Here”, 90 Michigan State Law Review, 2017, pp. 659–726.

[2] . Gaskin, Sam: “When Art Created by Artificial Intelligence Sells, Who Gets Paid?”, Art Market, September 17, 2018 (https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-art-created-artificial-intelligence-sells-paid).

[3] Sawyer, Robert Keith: Explaining Creativity – The Science of Human Innovation, Oxford, Oxford University Press 2012.

[4] For an early account see Dreier, Thomas: “Creation and Investment: Artistic and Legal Implications of Computer-generated Works”, in: Leser, Hans G.; Isomura, Tamotsu, Wege zum japanischen Recht. Festschrift für Zentaro Kitagawa zum 60. Geburtstag, Berlin, Duncker & Humblot 1992, pp. 869–888.

[5] E-David takes pictures autonomously with its camera and draws original paintings from the snapshots. By using different techniques, it makes “autonomous and unpredictable decisions about the image, the shapes and colors, the match of lights and shadows”; see Yanisky-Ravid, quoted, at 669.

[6] See Hodgkins, Kelly: “A British artist spent 10 years teaching this robot how to draw, and it totally shows”, Digitaltrends, 2016, https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/robotic-artist

[7] A generative adversarial network (GAN) is a machine learning model, invented by Ian Goodfellow in 2014, in which two neural networks compete with each other to become more accurate in their predictions. GANs typically run unsupervised.

[8] Christie’s: “Is artificial intelligence set to become art’s next medium?”, 2018, www.christies.com/features/A-collaboration-between-two-artists-one-human-one-a-machine-9332-1.aspx

[9] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, “Society, culture, and person: A systems view of creativity”, in: Sternberg, Robert: The Nature of Creativity – Contemporary Psychological Perspectives, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1988, pp. 325–339.

[10] The following definitions are provided by Jennings: “autonomous evaluation requires that the system be able to issue opinions without consulting an outside human or machine intelligence. However, the system is free to ask for or observe others’ opinions at other times, and to store this information”, Jennings, Kyle, “Developing Creativity. Artificial Barriers in Artificial Intelligence”, 20 Minds & Machines, 2010, pp.489–501.

[11] Jennings, Kyle, quoted, at p. 499.

[12] Ibidem.

[13] Ibidem.

[14] Moss, Richard: “Creative AI: the robots that would be painters”, 2015, https://newatlas.com/creative-ai-algorithmic-art-painting-fool-aaron/36106/

[15] Elgammal, Ahmed et al.: “Creative Adversarial Networks Generating “Art” by Learning About Styles and Deviating from Style Norms”, arXiv: 1706.07068v1 [cs.AI] (2017) pp. 1-22.

[16] See, among many: Zemer, Lior: The Idea of Authorship in Copyright, Routledge, London, 2016.

[17] U.S. Copyright Office: Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3d ed. 2017, https://copyright.gov/comp3/

[18] 499 U.S. 340, 1991.

[19] ECJ, case C-5/08 of 16 July 2009.

[20] Denicola, Robert C.: “Ex Machina. Copyright Protection for Computer-Generated Works”, 69 Rutgers University Law Review, 2016, pp. 251–287.

[21] Ramalho, Ana: “Will robots rule the (artistic) world? A proposed model for the legal status of creations by artificial intelligence systems”, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2987757

[22] A programmer (also calle coder) is an individual that writes computer software or applications by giving the computer specific programming instructions.

[23] Users are the people (or other systems) for whom the software is written.

[24] See Pagallo, Ugo: The Law of Robots. Crime, Contracts and Torts, Springer, Dordrecht, 2013.

[25] Davies, Colin R.: “An Evolutionary Step in Intellectual Property Rights. Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property”, 27 Computer Law & Security Review, 2011, pp. 601–619.

[26] 2018/2088 (INI).

[27] Ibidem.